The Dead Sea Scrolls: Psalms

by James Duguid | December 29, 2025

In my last post on the Dead Sea Scrolls, I looked at the Genesis scroll that is visiting the District of Columbia, 4QGeng. I set out some basics of text criticism (look back at that post if you need help with some of the details here), and I pointed out that this Genesis scroll is not that interesting in the grand scheme of things – for the eleven verses of Genesis it covers, it doesn’t record any variant readings that significantly change the interpretation.

Things are otherwise for the Psalms scroll that has come to visit, 4QPsa. For one thing, it is much longer than eleven verses. What remains of the scroll contains parts of nineteen psalms, stretching from Psalm 5 to Psalm 69 (when intact, it probably contained the whole psalter). In what is preserved, it records many variants. Some are like the variants we noted for the Genesis scroll, making little difference to meaning (note that English and Hebrew versification differs for the Psalms – I will use the English). So, one word in Psalm 38:16, “they may boast,” is in the imperfect, rather than a modal use of the perfect – this is difference of one letter, but has the same meaning (This reflects an adaptation of a rare, archaic grammatical form to one that was more well-known to Hebrew speakers of the day). In Psalm 69:4, the noun for “hairs” has a masculine rather than feminine form, which is interesting for Hebrew grammarians studying noun gender, but doesn’t change the meaning.

However, many of the variants are more significant. For starters, not all the psalms are in the same order. Psalm 32 is missing – this psalter runs straight from Psalm 31 to Psalm 33. Meanwhile, Psalm 71 immediately follows Psalm 38, in fact, they are treated as a single psalm (separate psalms have a blank line between them in this manuscript). Nor is this the only psalter from the Dead Sea Scrolls with differences of order. 11QPsa attests to several differences in order for the latter half of the psalter, as well as some extra psalms. It’s just possible that our scroll and this other one witness to the same psalter edition – they don’t overlap, so we can’t be sure. But there seems to have been at least one alternative psalter order used at Qumran.

Scholars disagree as to the significance of this. For some, it shows that the psalter was in flux – not a finished product even at this late point. Thus, it is argued, the psalter as we know it did not exist. On the other hand, the actual text of the individual psalms varies much less than the order of psalms. So the individual psalms may have been textually fixed even if there was some play with different editorial orders. Some scholars argue that the identical order of the Masoretic Text and the Old Greek (with only one extra psalm attested in the Old Greek, placed at the end) is strong evidence that the Masoretic Text preserves the oldest order, and that the Old Greek and Qumran versions are re-editings of this psalter. I find this argument convincing. Drew Longacre has a good discussion of these theories for those who want to go deeper.

Do merely editorial order changes affect the meaning of a psalm? Arguably, yes. Precisely why the psalms have been ordered as they do is a matter of scholarly debate, but there does seem to be some method to it. To a certain extent, the meaning of a particular psalm is relatively fixed as an individual unit – but dimensions of meaning do emerge depending on how it is juxtaposed with different psalms. And obviously if we fuse two psalms together, as with Psalm 38 and 71 in 4QPsa, this will make some difference to the meaning.

It will no doubt also be of interest to the readers that there are extra psalms added in various Qumran psalters. Some of them are attested elsewhere – thanks to the Dead Sea Scrolls, we have the original Hebrew for Psalm 151, preserved in the Old Greek. Psalms 154 and 155 are preserved in the Syriac Peshitta as well as the Dead Sea Scrolls. Thus, these psalms all are or have been considered canonical by some Christian groups. I’ve linked to translations of them so readers can take a look. An exercise for the reader: how would your theology change, if at all, if you accepted these compositions as the Word of God?

Moving on from the issues of differing order and extra psalms, 4QPsa witnesses to a number of interesting textual issues. Here are the ones I consider most interesting. In what follows, refer back to my previous post for a list of witnesses. On top of those, I also mention here Aquila and Symmachus, the authors of later revised editions of the Greek which tend to conform it to the proto-Masoretic Text.

- Psalm 35:27 in the Masoretic Text reads “May those who desire my vindication shout and rejoice, may they say continually, ‘Yahweh be praised, the one who desires the well-being of his servant.’” But in the Old Greek it reads “May those who desire my vindication shout and rejoice, may they say continually, ‘Yahweh be praised,’ those who desire the well-being of his servant.” 4QPsa preserves only the words “those who desire the well-being….” This change from singular to plural changes the referent of the phrase. In the singular, it must describe God, but in the plural, it describes members of the community who are on the psalmist’s side. The Vulgate, Peshitta, and Targum support the Masoretic Text here.

- Psalm 36:4 in the Masoretic Text reads, “He ponders wickedness on his bed, he takes his stand on a way not good, he does not reject evil.” 4QPsa reads, “...his bed, he counsels himself with every way n[ot…].” The Vulgate, Peshitta, Targum, and Symmachus support the Masoretic Text here. The Old Greek reads for this clause, “he takes his stand on every way not good,” agreeing with the Masoretic Text about which verb is used, but with 4QPsa about the presence of the term “all/every.” It is possible to propose multiple paths whereby the reading of the Masoretic Text or 4QPsa generates the others via a typo followed by unsuccessful attempts by scribes to guess the original, and it is genuinely difficult to pick the better reading.

- Psalm 38:20 in the Masoretic Text reads, “And those who repay evil instead of good oppose me in exchange for my pursuing good.” In 4QPsa the verse reads, “Those who repay evil instead of good plunder me in exchange for a good thing.” There are several differences here. 4QPsa lacks the conjunction “and” at the beginning of the verse, it has the term “plunder” instead of “oppose” (a one letter difference), and it has the term “thing” instead of “my pursuing” (a significant difference not explicable as a simple typo). The Old Greek here supports 4QPsa in the lack of “and,” but supports the Masoretic Text in the terms “oppose” and “my pursuing” (it also has a unique addition, “and they toss away me, the beloved, like a loathsome dead one”). The Vulgate, Peshitta, Targum, Aquila and Symmachus support the Masoretic Text here.

- Psalm 54:3 in the majority of Masoretic manuscripts reads, “For strangers have risen against me, and violent ones seek my life; they have not placed God before them,” but many Masoretic manuscripts read “presumptuous ones” instead of “strangers,” a difference of one letter (the two letters are very easily confused). 4QPsa reads “strangers have risen against me.” The Old Greek, Vulgate, Peshitta, and one Targum manuscript have “strangers,” while most Targum manuscripts have “presumptuous ones.”

- Psalm 69:3 in the Masoretic Text reads, “I am weary of calling out, my throat is hoarse, my eyes have worn away waiting for my God. 4QPsa reads, “[...I am weary of calling out,] my [throat is hoarse,] my teeth have worn away writhing for the God of Is[rael] (or possibly: of [my] sa[lvation]). What body part is wearing out – the eyes from crying or the teeth from gnashing? Is the activity “waiting” or “writhing?” Either of these differences could have arisen from a one-letter change. The different title for God is a more substantial edit. The Old Greek, Aquila, Symmachus, Vulgate, Peshitta, and Targum all support the Masoretic Text on these issues.

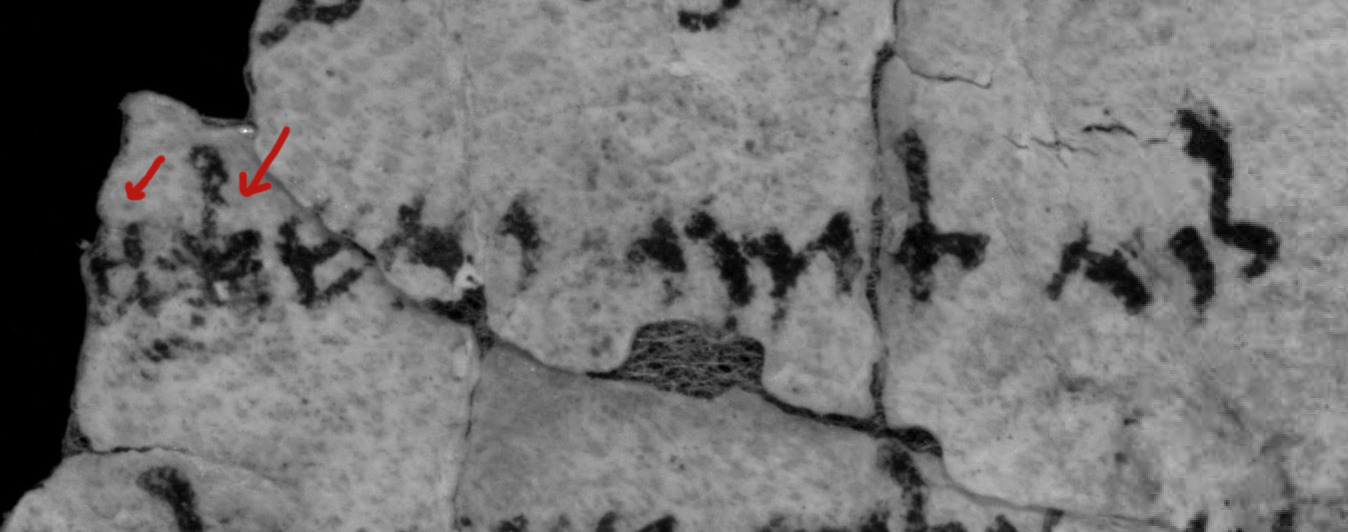

- Psalm 69:5 in the Masoretic Text reads, “O God, you know my folly, and my guilt is not hidden from you.” 4QPsa reads [… O God,] you know I have not borrowed that I should repay i[t…]. This is, needless to say, quite different, changing a confession of sin into a protestation of innocence, in line with “what I have not stolen” from the previous verse. If spelled compactly, “my folly” may become “I have not borrowed” by transposition of a single letter and joining of two words into one. As for “my guilt,” it is in fact what was first written in 4QPsa, but it has been corrected with two letters written over top of it (if you cannot read Hebrew, you can at least see that there is a mess!). The Old Greek, Symmachus, Vulgate, Peshitta, and Targum support the Masoretic Text.

- Psalm 69:14 in the Masoretic Text reads, “Deliver me from the mud, and let me not sink, that I might be delivered from those who hate me and from deep waters.” 4QPsa reads, “Deliver me from the mud, [and] let me not sink, that the one who robs me might take me, [del]iver me from those who hate me, deep waters.” Besides the change in conjugation of “deliver me,” 4QPsa has a clause missing in all other versions. The Old Greek, Vulgate, Peshitta, and Targum support the Masoretic Text.

- Psalm 71:6 in the Masoretic Text reads, “On you I have leaned from the womb, you were the one who cut me from the belly of my mother, in you is my praise always.” Is this describing God as the one who cut David’s umbilical cord? 4QPsa reads, “On you I have leaned from [the womb,] from the belly of my mother you were my strength, in you [is my praise always]” – this would be a difference of one letter, and a much more conventional name for God. The Targum has “you are the one who pulled me out from the womb of my mother,” another one letter change which gives a term known from Psalm 22:9 in this sense. Incidentally, there is a Coptic version with the same translation; since the Coptic was translated from the Greek, this implies the existence of some Greek version that translated this way as well. The Peshitta has “confidence,” which, however it is getting there, is also how it translates Psalm 22:9, so presumably it is also making the same move as the Targum. Do these translators actually have a manuscript with this reading, or are they simply conforming their translation to Psalm 22:9? The Vulgate has protector, which is how Jerome usually renders a term for “fortress” with only one letter difference from the word for “strength” in 4QPsa; one wonders if his manuscript had this, or he was stumped by the reading in the Masoretic Text and guessed. The Old Greek translates “shelterer,” but this may simply be a guess. Symmachus has “you have looked upon me” – perhaps he is guessing based on Psalm 139:16. It seems that everyone had a difficult time with this one.

All of these examples change the meaning of the verse they are in, to a greater or lesser extent. Readers may notice that the Peshitta, Vulgate, and Targums usually agree with the Masoretic Text. Does this not mean we should always follow the Masoretic Text, since it has this preponderance of supporters? But remember that the popularity of the Masoretic Text peaked in the century leading up to Christ. These translations are all based on descendents of a few or even one standard proto-Masoretic copy from this time, so they don’t really count as separate witnesses when they agree. In text criticism, we say that witnesses must be weighed, not counted. The majority does not always win. In the case of the Old Testament, the Old Greek and some of the Dead Sea Scrolls are based on text types that diverged from the proto-Masoretic Text long before it became the standard which then dominated later copying. Thus, they count for more.

In keeping with this, the example from Psalm 35:27 shows us a place where the Old Greek disagrees from the Masoretic Text with all the later translations, but it supported by 4QPsa. This is a strong argument for the authenticity of this reading. If we didn’t have the Dead Sea Scrolls, we would end up with a tie between the Old Greek and the Masoretic Text, and we would need to rely on arguments about which reading made most sense in context.

For the example in Psalm 54:3, on the other hand, the textual issue there survived the proto-Masoretic Text bottleneck, and is witnessed by different Masoretic manuscripts, as well as by the manuscript used for the Targum’s translation. 4QPsa gives evidence supporting the reading of the majority of Masoretic manuscripts, alongside the Old Greek – this is strong evidence for the reading.

For Psalm 71:6, on the other hand, the Masoretic Text, 4QPsa, and the Old Greek all seem to go different ways, making it difficult to decide on the best reading. It may be that we should accept the Masoretic Text as the strangest reading – all the others can be explained as harmonizations of this reading to accepted ideas in other passages (that is, provided we don’t find the Masoretic Text entirely too weird to accept).

The variants in Psalm 69 are the most interesting. 4QPsa preserves readings that are found nowhere else. Perhaps they should be dismissed, since the Old Greek and the Masoretic Text line up against them. And yet, some of them seem like they might fit the passage better, and I think they should at least be entertained. The variant in Psalm 69:5 changes a confession of sin into a protestation of innocence. It doesn’t only change the meaning of the verse, but would change how we read the whole psalm, since it seems to identify David’s predicament as being accused of defaulting on a loan. Admittedly, it doesn’t completely change the meaning of the psalm – it doesn’t make David’s enemies innocent, or say that David doesn’t want help from God, or anything like that. Much of what the psalm has to say is the same in all versions. But the precise nature of David’s trouble, and whether or not he has any culpability in it, is hardly an incidental detail. My decision on this textual issue might change how I would preach the psalm.

Many of these meaningful changes identified in this scroll make a minimal difference to the psalm as a whole. I know from the rest of Psalm 35 that God will vindicate David, and that the community of the faithful will celebrate this, whichever point the debated clause is making. From these examples though, we can see that text criticism does sometimes make a significant difference to the meaning of a passage. If we want to study Scripture carefully and closely, we will need to pay attention to it.